Winter count at the National gallery

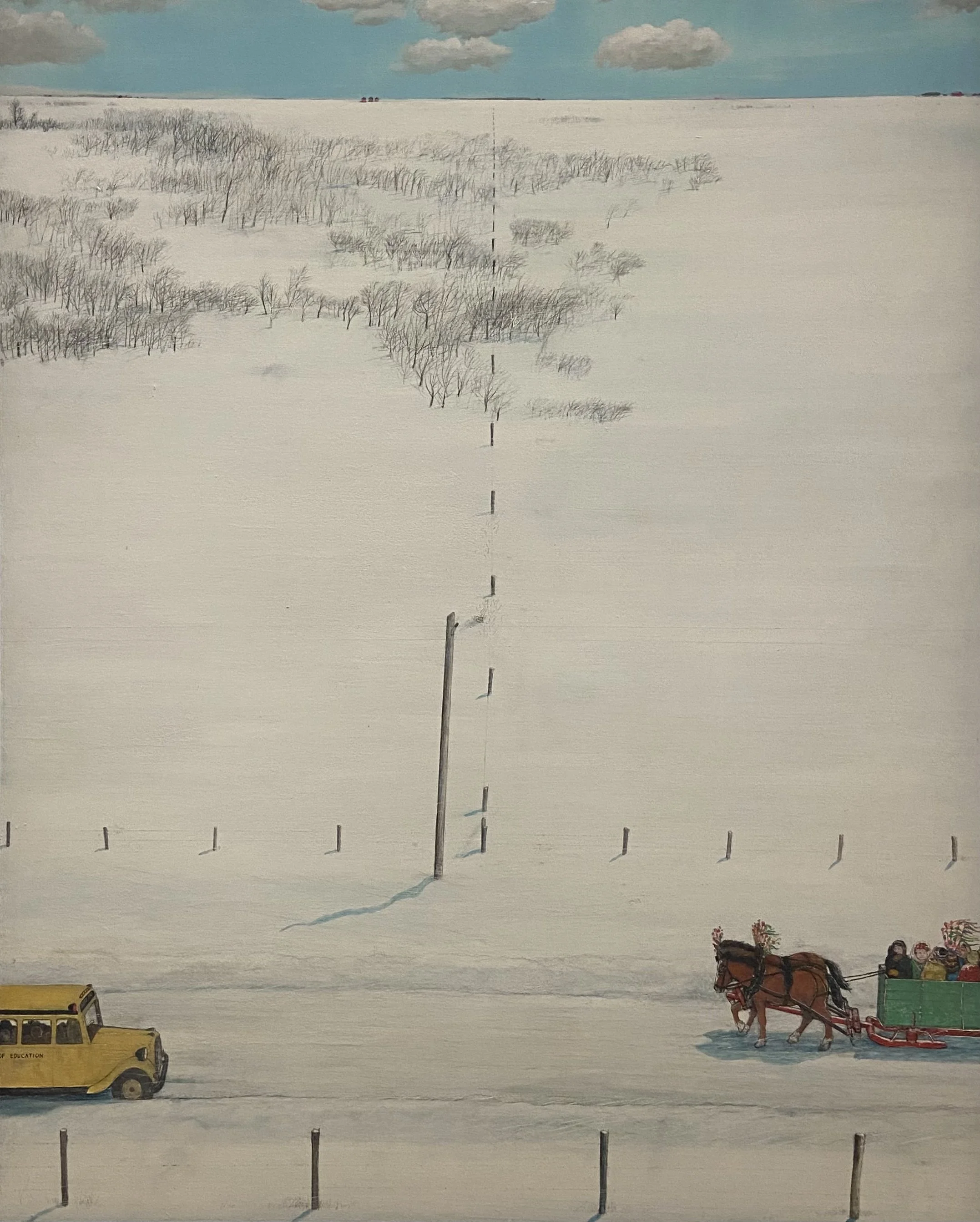

William Kureluk’s The Ukrainian Pioneer No. 5 (c. 1970s)

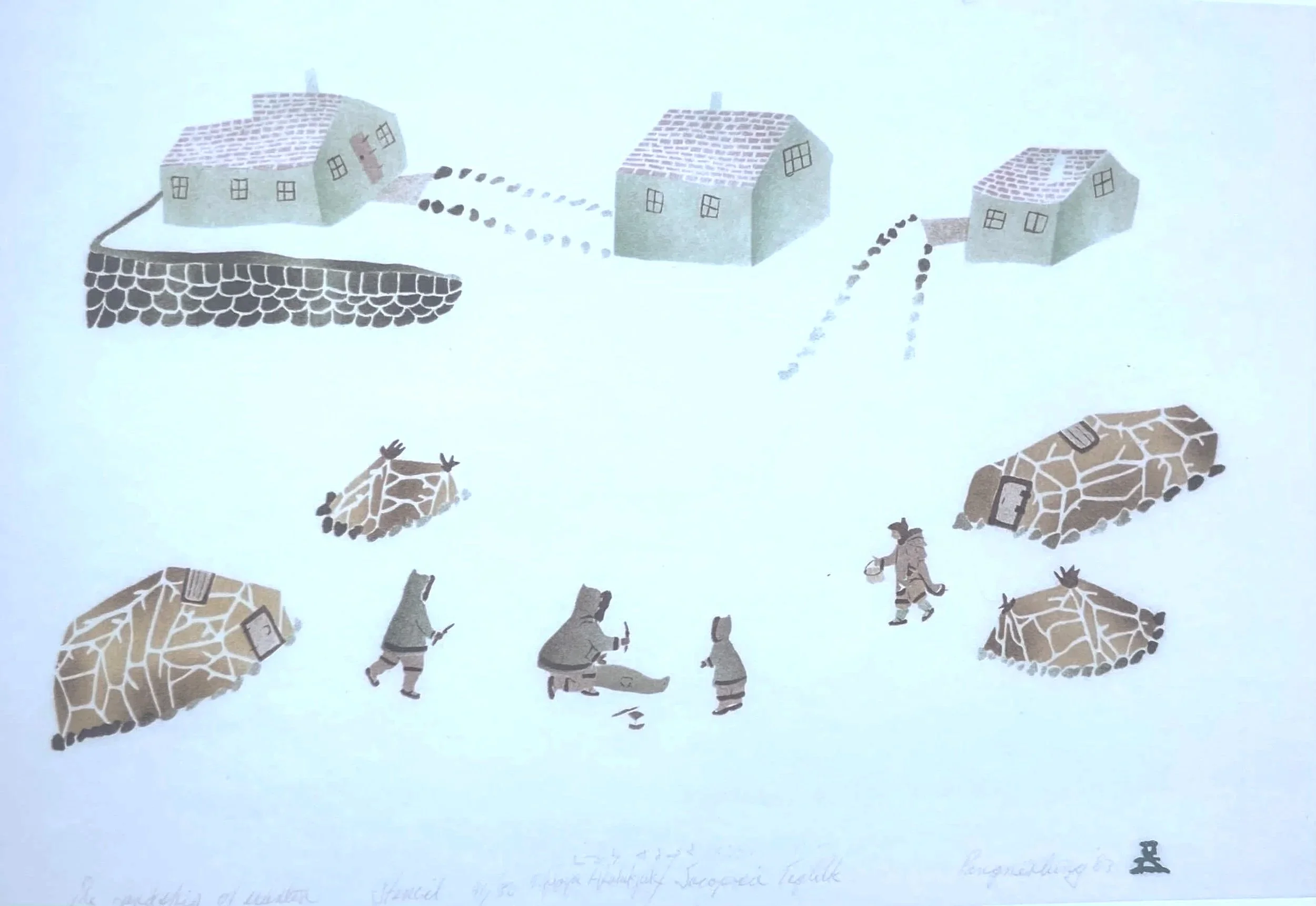

Malaya Akulukjuk’s The Hardship of Winter (1983)

Gustave Courbet’s Fox in the Snow (1860)

Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté’s The Blessing of the Maples (1915)

Jessica Winters’ December 24th (2024)

Claude Monet’s Morning Haze (1894).

Karl Fredrik Nordström’s Clear Evening in Late Winter (1907)

Harald Viggo, Aurora Borealis over Iceland in works from 1889–90

Marja Helander’s Imatra, Snow (2010)

Duane Linklater’s hanging installation Winter Count (2023)

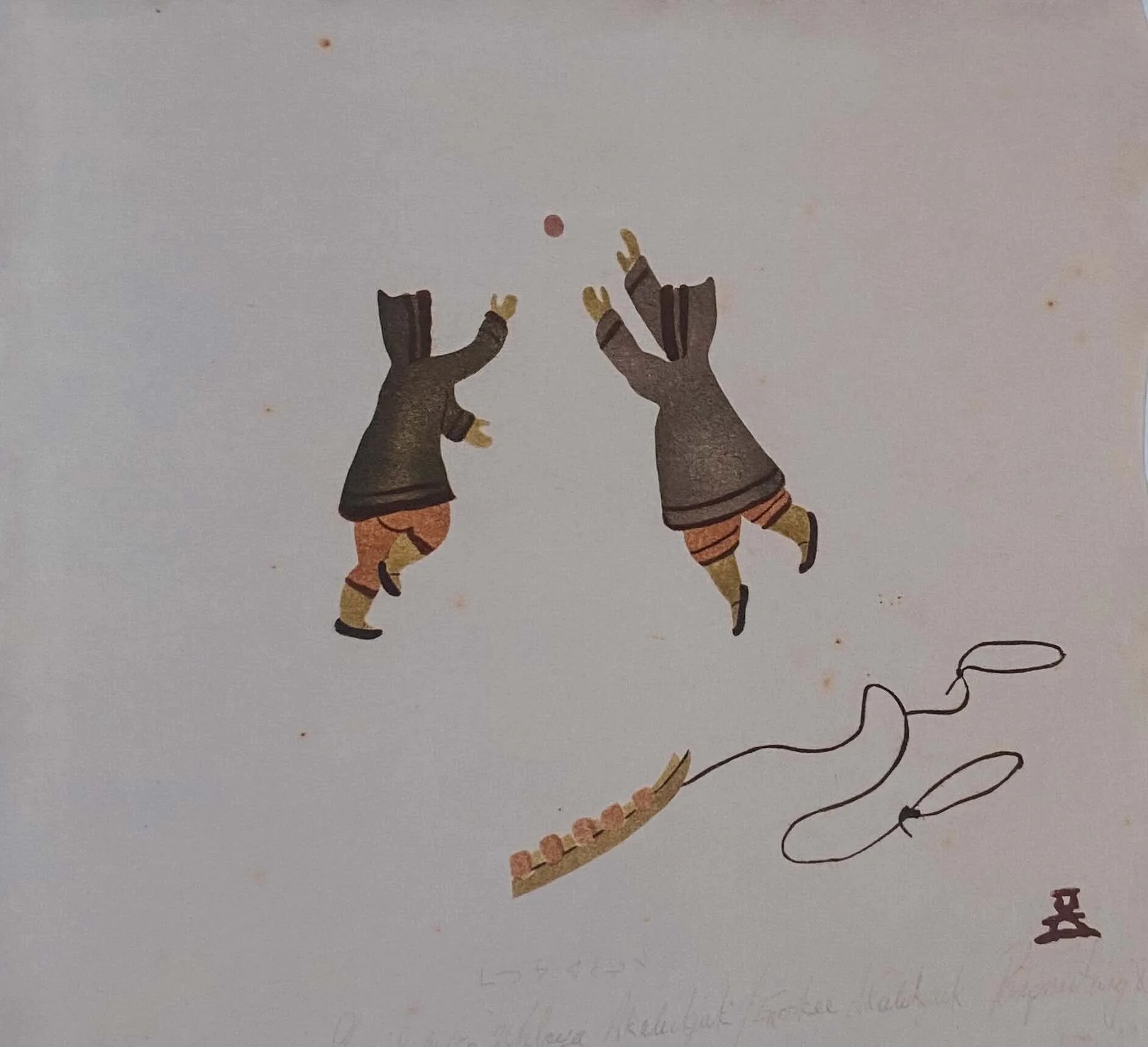

Malaya Akulukjuk’s Winter Games (1983)

Annie Pootoogook’s Christmas (2006)

Child’s kamik (boot) (1968)

Snow goggles, or iggaak, Inuit dating from approximately 300–500 AD.

Detail of Bruno Liljefors’ A Running Hare (1892)

Wassily Kandinsky’s Murnau with Locomotion (1911)

Wassily Kandinsky’s Winer Near Urfeld (1908)

Lawren Harris’ Icebergs, Davis Strait. (1930)

Doris McCarthy’s Iceberg Fantasy before Bylot (1974)

A recent trip to Ottawa for a delivery gave me the perfect opportunity to visit Winter Count: Embracing the Cold at the National Gallery of Canada. The exhibition is one of the most thoughtful and richly layered I’ve seen in recent years. On view until March 22, 2026, it brings together over 150 works spanning the early 19th century to today, creating a compelling dialogue between Indigenous, Canadian settlers, and European approaches to the experience of winter.

What struck me most is how the curators treat winter not simply as a landscape or a season, but as both a physical force and a cultural metaphor. The exhibition explores winter as a shared yet varied human experience—one that encompasses survival, memory, resilience, and community. The title references the Winter Count tradition of Plains Indigenous nations, where annual events were recorded visually on hides, marking not just time but collective history. In this tradition, a person’s age is not measured in years, but by the number of winters they have lived—a profoundly seasonal and cyclical way of understanding life.

The exhibition is creatively divided into themed sections, each examining a different facet of winter: The Stories We Tell, Winter Light, Winter Night, Winter Count, Community and Isolation, The Body Transformed, The Blanket of Snow, and Abstraction.

Under The Stories We Tell, I was particularly struck by two works that present winter from distinct cultural perspectives. William Kureluk’s The Ukrainian Pioneer No. 5 (c. 1970s) reflects winter from a settler viewpoint, while Malaya Akulukjuk’s The Hardship of Winter (1983) offers an Indigenous perspective. Both works speak powerfully to endurance, spirit, and the deeply personal histories embedded in winter life.

Other paintings in this section that I found delightful for their brushwork and execution include Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté’s The Blessing of the Maples (1915) and Gustave Courbet’s Fox in the Snow (1860). The loose brushstrokes and texture in Courbet’s painting—something I particularly appreciate as an encaustic artist—verge on abstraction in the background, adding depth and movement that make the winter landscape feel alive and tactile. Each of these works communicates winter differently, from lyrical light and color to stark realism, yet all share a strong sense of human presence within the season.

Moving on to Winter Light, I was again struck by a work by an artist I was less familiar with but immediately drawn to: Settled on the Hillside (1909) by Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté. Any artist who has painted shadows on snow will appreciate the subtle blues and purples in this piece. And of course, one can never pass by a painting by Claude Monet without lingering; I spent a long moment with Morning Haze (1894).

The next section, Winter Night, was—unsurprisingly—my favourite. Artists like myself are often drawn to the visual transformations that occur at night, when familiar landscapes become new and challenging subjects. This was certainly the case with Swedish artist Karl Fredrik Nordström’s Clear Evening in Late Winter (1907). The texture of the dark night sky is almost encaustic in texture, with stars forming a quiet constellation.

Canadian artist Franz Johnston’s A Northern Light (1917), part of the National Gallery’s permanent collection, is a lesson in restraint and simplicity. This tempera painting shows a snowy landscape lit by the northern lights, with two tiny figures that subtly evoke human vulnerability in the face of nature. Danish artist Harald Viggo Moltke captures the elusive beauty of the Aurora Borealis over Iceland in works from 1889–90 with remarkable sensitivity.

Moving into more contemporary work, Inuit artist Jessica Winters’ December (2024) is a marvel of composition and light. And while I have a strong inclination toward painting, I was also struck by the work of Finnish-Sámi photographer Marja Helander. Her photograph Imatra, Snow (2010), depicting deserted gas station pumps glowing in the winter night, is mounted on aluminum and carries a quiet, unsettling beauty. Further research revealed that her work often explores the tension between nature and human industry—a theme that resonates deeply in this piece. If you have a moment, I highly recommend watching her short film Birds in the Earth.

Solidifying the exhibition is Cree artist Duane Linklater’s hanging installation Winter Count, composed of canvas, cochineal, orange pekoe tea, charcoal, sumac, cotton thread, and blueberry dye. Acquired by the National Gallery in 2023, the work references Omaskeko Cree culture, where a person’s age is not measured in years but by the number of winters they have lived. The materials themselves carry a sense of land, labour, and time, anchoring the exhibition’s central themes in lived experience and Indigenous knowledge.

In the Community and Isolation section of the show, I was particularly struck by Malaya Akulukjuk’s Winter Games, along with Christmas (2006) by one of my favourite Indigenous artists, the late Annie Pootoogook. Both works beautifully illustrate the activities and rhythms of life during long northern winters, emphasizing connection, routine, and shared experience rather than hardship alone.

Moving on to The Body Transformed, the exhibition reminds us of the frigid temperatures of the northern hemisphere and how Indigenous communities have long combined technological innovation with artistic vision in response to extreme climates. This is especially evident in the garments on display. One of my favourites was a child’s kamik (boot) (1968), made of bearded seal skin and harp seal skin with painted cotton on textile, on loan from the Bata Shoe Museum. Intricately decorated, these boots are not only visually striking but also beacons of warmth and care—designed to protect a young child while reflecting cultural identity and craftsmanship.

Continuing with the theme of winter technology, the exhibition also includes snow goggles, or iggaak, dating from approximately 300–500 AD. Carved from ivory by Alaska Inuit living in the Arctic, these early goggles functioned much like modern sunglasses, protecting the eyes from snow blindness caused by intense glare. Both beautifully designed and highly practical, they are a striking reminder of the deep knowledge, innovation, and adaptability Indigenous peoples developed in response to extreme winter conditions.

The Blanket of Snow section exemplifies artists’ depictions of snow in all its forms—from the gently fallen snowflake to heavy, snow-laden branches—focusing on colour, texture, form, and weight. Swedish artist Bruno Liljefors’ A Running Hare (1892), oil on canvas, beautifully captures life moving both on and beneath the snowy layers, conveying a vivid sense of motion and survival within the winter landscape.

The final section of Winter Count is Abstraction, where artists push the boundaries of the winter landscape by stretching natural forms to the furthest point of recognition. I was particularly captivated by Wassily Kandinsky’s Murnau with Locomotion (1911), a precursor to his more fully abstract work in the years that followed. This was shown in contrast to the small, intimate painting by Kandinsky Winter near Uflede, where snow appears with very little white, instead revealing subtle hues of blue, pink, grey, and yellow.

And of course, no exhibition devoted to winter would feel complete without the inclusion of Doris McCarthy and Lawren Harris. Their iceberg paintings provide a fitting conclusion to the journey—moving fully into winter abstraction and reinforcing how ice, snow, and cold have long inspired artists to explore form, colour, and spiritual presence.

If you’re at all open to the artistic importance of winter, do yourself a favour and visit the National Gallery in Ottawa before the show closes on March 22. I promise—you’ll never look at shovelling snow the same way again.

-Susan Wallis